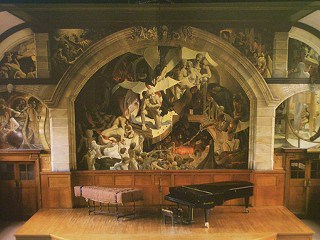

Figure 1: The Hall of Illusion (1993) by Ed Povey, 20′ x 40′ mural in Neuadd Powis/Powis Hall, Bangor University, Gwynedd, North Wales. https://www.austinchronicle.com/arts/2009-05-22/784579/

Having completed a cycle of reflective posts, I find myself closing the circle with an exploration of the surreal world of art, both within and beyond the confines of the gallery machinery. It is the world I wanted to reach at the beginning of this journey, but in true ‘Looking Glass’ style, I was obliged to approach it obliquely, through a series of chance encounters. As I move on to another stage of my practice, it is appropriate that I close this book and open another. However, I intend to continue updating this blog as a dynamic part of my ongoing development, a new kind of ‘sketchbook’. I have noted dramatic growth in my knowledge and awareness in this active process of reading, writing and reflection. It has also fed into my practice and completely transformed my approach.

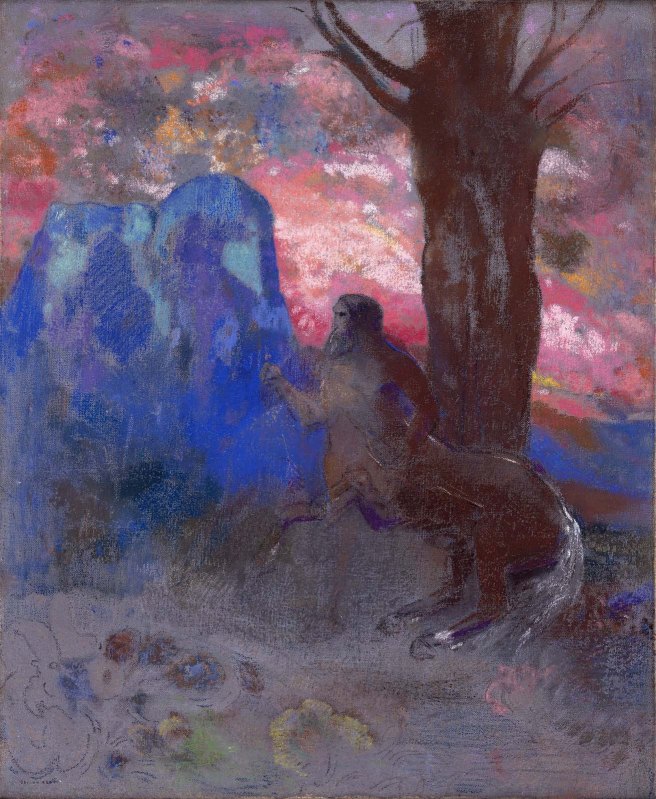

The next stage of my practice will involve a consideration of audiences and this has been a topic very much to the fore in my recent visits to exhibitions. I always remember something that an American colleague from South Jersey, New York State told me some years ago, about going to Central Park for the day to see Christo’s installation, The Gates in 2005 (http://christojeanneclaude.net/projects/the-gates). She was not an artist, or involved in the art world in any way, but Christo’s outdoor installation made people from all walks of life come and look. Not everyone liked it, but it was the talk, not just of the city, but of the wider world. Further back in my life, I remember Ed Povey’s colourful, poetic murals, bringing grey facades and ends of terraces to life (see Figure 2, below). Many have since disappeared, but Povey returned in the early ‘90s to create a masterpiece in the University’s auditorium (see Figure 1, above). The Hall of Illusion is now the backdrop to final exams, concerts and conferences, but to get to this place, Povey took one step, and then another, and then another…

Figure 2: Murals on College Road, Bangor, mid-’70s. https://www.bangor.ac.uk/alumni/photo.php.en

Art that people travel to see also makes me think about the standing stones, circles and ancient landscape art all around Britain: the sense of place, the connections created. They are objects, but also performance, through their interaction with those who visit them. The same could be said of street art – it is intended for its context. Therefore, removing it as a commodity to be transplanted somewhere else changes it entirely, perhaps even extinguishes it entirely. Moreover, despite the fact that most street art is distinctly ‘outsider’, on pretty much every level one could think of, the general public and art world often fight to preserve it. For instance, Banksy’s murals attract a crowd, and in his home city of Bristol, the local Council caved in under public pressure to leave his graffiti where it was (Logan, 2008). A browse through a few examples of the most famous (infamous?) street artists will reveal the full gamut of public reaction: celebration, anger, opportunism, activism, curiosity, admiration… but never indifference (Time, 2016).

In light of the above, three things of importance have emerged for me during this enquiry:

- The creation of spaces, maybe to escape into, because things are ‘better’ or more interesting ‘over there’. Many of the artists and illustrators who have fascinated me in my life have done this, whether in the creation of fantasy worlds, surreal universes or intriguing landscapes and interiors. I have found this reflected in my practice. Spaces are where things can happen, they create opportunities. Sometimes we have to fight for them and expand our borders.

- Authenticity, or the artist’s commitment to the work they develop, whether based on a rationale, or on their own particular creative incentives. If integrity is a desirable and even necessary quality in other professions, then why should the creative arts be any different? An artist with integrity will inevitably break new ground, because they will push towards development. They will also seek excellence. This can take different forms, but without compromise.

- Audiences, as opposed to markets. This is not denying the legitimacy of making a living from art, but rather being aware of art as communication. Awareness of the audience(s) as opposed to the market leads to greater relevance and quality. It is a particularly interesting factor to consider, as it invites an enquiry into wider issues. It is also significant for me, because audiences are not a consideration that is native to Fine Art.

To conclude, this current blog topic has brought me over several bridges and its beginnings already seem far behind me. Therefore, the thought of ending here and not making this a core tool of my practice seems unthinkable now. Reflection is a discipline, just like drawing; it means standing still, clearing a space, allowing things to happen.

References:

http://www.bangor.ac.uk (n.d.) ‘Snapshot of Bangor’, Development and Alumni Relations Office [website]. https://www.bangor.ac.uk/alumni/photo.php.en [Accessed 12 December, 2017]

Faires, R. (2009) Not Weird But Real, May 22. https://www.austinchronicle.com/arts/2009-05-22/784579/ [Accessed December 12, 2017].

Logan, L. (2008) ‘Banksy defends his guerrilla graffiti art’, TIME, 29 Oct. http://content.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,1854616,00.html [Accessed 8 December, 2017].

TIME (2016) Top 10 Guerrilla Artists http://content.time.com/time/photogallery/0,29307,1911799,00.html [Accessed 8 December, 2017].

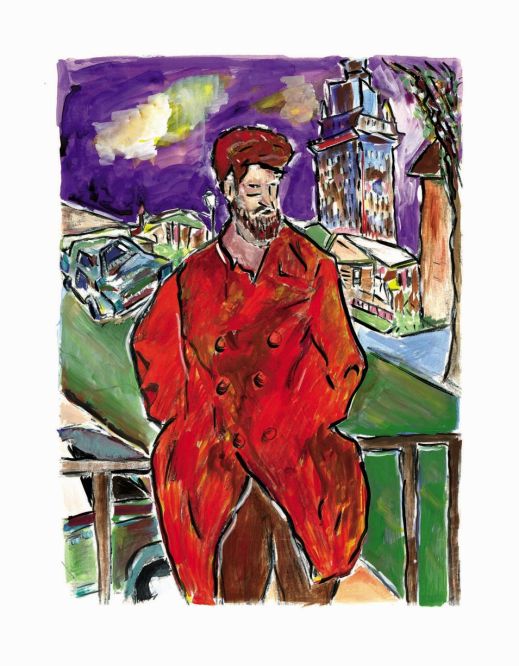

Figure 1: ‘Man on a Bridge’ (2008) by Bob Dylan from the Drawn Blank series (hand-signed limited edition print, courtesy of Castle Fine Art, Cardiff)

Figure 1: ‘Man on a Bridge’ (2008) by Bob Dylan from the Drawn Blank series (hand-signed limited edition print, courtesy of Castle Fine Art, Cardiff)

Figure 2: Source: Williams (1979)

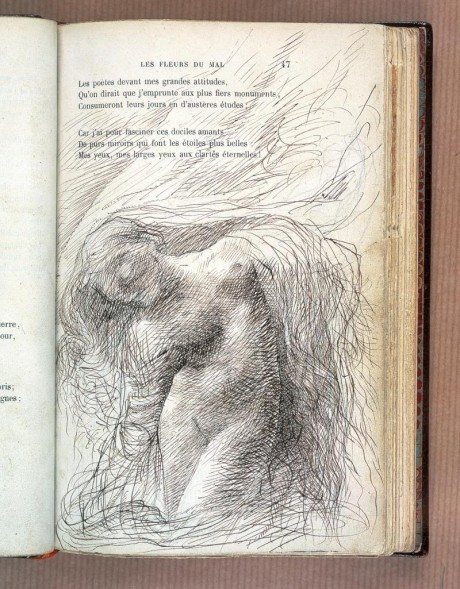

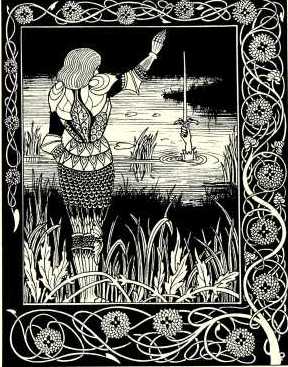

Figure 2: Source: Williams (1979) Figure 3: Aubrey Beardsley (1893-1894) ‘How Sir Bedivere Cast the Sword Excalibur into the Water’ [illustration]. Le Morte Darthur, J. M. Dent & Co., London.

Figure 3: Aubrey Beardsley (1893-1894) ‘How Sir Bedivere Cast the Sword Excalibur into the Water’ [illustration]. Le Morte Darthur, J. M. Dent & Co., London. Figure 4: Mark Wilkinson, (2005) Bouillebasse.

Figure 4: Mark Wilkinson, (2005) Bouillebasse.

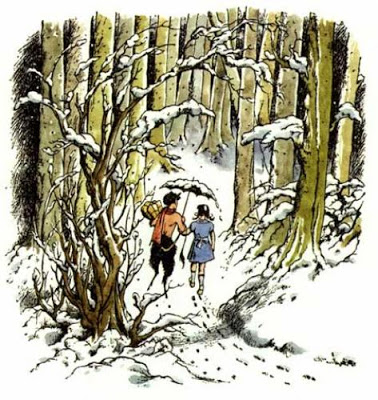

Figure 2: Illustration by Pauline Baynes for The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe (Lewis, 1950)

Figure 2: Illustration by Pauline Baynes for The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe (Lewis, 1950)